Wednesday 30 April 2008

Friday 25 April 2008

Machine Dreams: Economics Becomes a Cyborg Science

Editorial Reviews

"As history, Machine Dreams is a remarkable achievement. It is hard to imagine a historian who was not an economist (as Mirowski is) being able to encompass the economics of the second half of the 20th century in its diversity and technicality." London Review of Books

"Phil Mirowski reminds me of an investigative reporter with a world-class story. He has gone straight to the heart of a really interesting problem--the emergence of economics' modern era in the crucible of World War II--and come back with a detailed account of events at The Cowles Commission and the RAND Corporation. It is news, the best that can be said quickly. It is opinion: cyborg economics (meaning purely cognitive economics) is not the sort of science Mirowski wants to see. And it is sensationally interesting. You don't have to agree with his conclusions to recognize that Mirowksi is the most imaginative and provocative writer at work today on the recent history of economics. Machine Dreams is a real-time cousin to The Difference Engine ." David Warsh, The Boston Globe

"Machine Dreams is an astonishing performance of synthetic scholarship. Mirowski traces the present-day predicaments of economic theory to its intellectual reformulation and institutional restructuring by military funding and in the crucibles of World War II and the Cold War. His demonstration that the mathematical economics of the postwar era is a complex response to the challenges of "cyborg" science, the attempt to unify the study of human beings and intelligent machines through John von Neumann's general theory of automata, is bound to be controversial. His critics, however, will have to contend with a breathtakingly wide range of published and unpublished evidence in fields ranging from psychology to operations research he presents. This noir history of economic thought will change its readers' understanding of twentieth century economics profoundly." Duncan Foley, New School University

"Machine Dreams is an astonishing performance of synthetic scholarship. Mirowski traces the present-day predicaments of economic theory to its intellectual reformulation and institutional restructuring by military funding and in the crucibles of World War II and the Cold War. His demonstration that the mathematical economics of the postwar era is a complex response to the challenges of "cyborg" science, the attempt to unify the study of human beings and intelligent machines through John von Neumann's general theory of automata, is bound to be controversial. His critics, however, will have to contend with a breathtakingly wide range of published and unpublished evidence in fields ranging from psychology to operations research he presents. This noir history of economic thought will change its readers' understanding of twentieth century economics profoundly." Duncan Foley, New School University

"In Machine Dreams the most exciting historian of economic thought of our time takes on one of the most fascinating themes of the intellectual history of the 20th century--the dream of creating machines that can think and how this has affected the social sciences. The result is an extraordinary book that deserves to be read by everyone interested in the social sciences." Richard Swedberg, University of Stockholm

Product Description

This is the first cross-over book in the history of science written by an historian of economics, combining a number of disciplinary and stylistic orientations. In it Philip Mirowshki shows how what is conventionally thought to be "history of technology" can be integrated with the history of economic ideas. His analysis combines Cold War history with the history of the postwar economics profession in America and later elsewhere, revealing that the Pax Americana had much to do with the content of such abstruse and formal doctrines such as linear programming and game theory. He links the literature on "cyborg science" found in science studies to economics, an element missing in the literature to date. Mirowski further calls into question the idea that economics has been immune to postmodern currents found in the larger culture, arguing that neoclassical economics has surreptitiously participated in the desconstruction of the integral "Self." Finally, he argues for a different style of economics, an alliance of computational and institutional themes, and challenges the widespread impression that there is nothing else besides American neoclassical economic theory left standing after the demise of Marxism.

Philip Mirowski is Carl Koch Professor of Economics and the History and Philosophy of Science, University of Notre Dame. He teaches in both the economics and science studies communities and has written frequently for academic journals. He is also the author of More Heat than Light (Cambridge, 1992) and editor of Natural Images in Economics (Cambridge, 1994) and Science Bought and Sold (University of Chicago, 2001).

Tuesday 22 April 2008

The Art of War

The attack conducted by units of the Israeli Defence Forces (IDF) on the city of Nablus in April 2002 was described by its commander, Brigadier-General Aviv Kokhavi, as ‘inverse geometry’, which he explained as ‘the reorganization of the urban syntax by means of a series of micro-tactical actions’.1 During the battle soldiers moved within the city across hundreds of metres of ‘overground tunnels’ carved out through a dense and contiguous urban structure. Although several thousand soldiers and Palestinian guerrillas were manoeuvring simultaneously in the city, they were so ‘saturated’ into the urban fabric that very few would have been visible from the air. Furthermore, they used none of the city’s streets, roads, alleys or courtyards, or any of the external doors, internal stairwells and windows, but moved horizontally through walls and vertically through holes blasted in ceilings and floors. This form of movement, described by the military as ‘infestation’, seeks to redefine inside as outside, and domestic interiors as thoroughfares. The IDF’s strategy of ‘walking through walls’ involves a conception of the city as not just the site but also the very medium of warfare – a flexible, almost liquid medium that is forever contingent and in flux.

Contemporary military theorists are now busy re-conceptualizing the urban domain. At stake are the underlying concepts, assumptions and principles that determine military strategies and tactics. The vast intellectual field that geographer Stephen Graham has called an international ‘shadow world’ of military urban research institutes and training centres that have been established to rethink military operations in cities could be understood as somewhat similar to the international matrix of élite architectural academies. However, according to urban theorist Simon Marvin, the military-architectural ‘shadow world’ is currently generating more intense and well-funded urban research programmes than all these university programmes put together, and is certainly aware of the avant-garde urban research conducted in architectural institutions, especially as regards Third World and African cities. There is a considerable overlap among the theoretical texts considered essential by military academies and architectural schools. Indeed, the reading lists of contemporary military institutions include works from around 1968 (with a special emphasis on the writings of Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari and Guy Debord), as well as more contemporary writings on urbanism, psychology, cybernetics, post-colonial and post-Structuralist theory. If, as some writers claim, the space for criticality has withered away in late 20th-century capitalist culture, it seems now to have found a place to flourish in the military.

I conducted an interview with Kokhavi, commander of the Paratrooper Brigade, who at 42 is considered one of the most promising young officers of the IDF (and was the commander of the operation for the evacuation of settlements in the Gaza Strip).2 Like many career officers, he had taken time out from the military to earn a university degree; although he originally intended to study architecture, he ended up with a degree in philosophy from the Hebrew University. When he explained to me the principle that guided the battle in Nablus, what was interesting for me was not so much the description of the action itself as the way he conceived its articulation. He said: ‘this space that you look at, this room that you look at, is nothing but your interpretation of it. […] The question is how do you interpret the alley? […] We interpreted the alley as a place forbidden to walk through and the door as a place forbidden to pass through, and the window as a place forbidden to look through, because a weapon awaits us in the alley, and a booby trap awaits us behind the doors. This is because the enemy interprets space in a traditional, classical manner, and I do not want to obey this interpretation and fall into his traps. […] I want to surprise him! This is the essence of war. I need to win […] This is why that we opted for the methodology of moving through walls. . . . Like a worm that eats its way forward, emerging at points and then disappearing. […] I said to my troops, “Friends! […] If until now you were used to move along roads and sidewalks, forget it! From now on we all walk through walls!”’2 Kokhavi’s intention in the battle was to enter the city in order to kill members of the Palestinian resistance and then get out. The horrific frankness of these objectives, as recounted to me by Shimon Naveh, Kokhavi’s instructor, is part of a general Israeli policy that seeks to disrupt Palestinian resistance on political as well as military levels through targeted assassinations from both air and ground.

If you still believe, as the IDF would like you to, that moving through walls is a relatively gentle form of warfare, the following description of the sequence of events might change your mind. To begin with, soldiers assemble behind the wall and then, using explosives, drills or hammers, they break a hole large enough to pass through. Stun grenades are then sometimes thrown, or a few random shots fired into what is usually a private living-room occupied by unsuspecting civilians. When the soldiers have passed through the wall, the occupants are locked inside one of the rooms, where they are made to remain – sometimes for several days – until the operation is concluded, often without water, toilet, food or medicine. Civilians in Palestine, as in Iraq, have experienced the unexpected penetration of war into the private domain of the home as the most profound form of trauma and humiliation. A Palestinian woman identified only as Aisha, interviewed by a journalist for the Palestine Monitor, described the experience: ‘Imagine it – you’re sitting in your living-room, which you know so well; this is the room where the family watches television together after the evening meal, and suddenly that wall disappears with a deafening roar, the room fills with dust and debris, and through the wall pours one soldier after the other, screaming orders. You have no idea if they’re after you, if they’ve come to take over your home, or if your house just lies on their route to somewhere else. The children are screaming, panicking. Is it possible to even begin to imagine the horror experienced by a five-year-old child as four, six, eight, 12 soldiers, their faces painted black, sub-machine-guns pointed everywhere, antennas protruding from their backpacks, making them look like giant alien bugs, blast their way through that wall?’3

Naveh, a retired Brigadier-General, directs the Operational Theory Research Institute, which trains staff officers from the IDF and other militaries in ‘operational theory’ – defined in military jargon as somewhere between strategy and tactics. He summed up the mission of his institute, which was founded in 1996: ‘We are like the Jesuit Order. We attempt to teach and train soldiers to think. […] We read Christopher Alexander, can you imagine?; we read John Forester, and other architects. We are reading Gregory Bateson; we are reading Clifford Geertz. Not myself, but our soldiers, our generals are reflecting on these kinds of materials. We have established a school and developed a curriculum that trains “operational architects”.’4 In a lecture Naveh showed a diagram resembling a ‘square of opposition’ that plots a set of logical relationships between certain propositions referring to military and guerrilla operations. Labelled with phrases such as ‘Difference and Repetition – The Dialectics of Structuring and Structure’, ‘Formless Rival Entities’, ‘Fractal Manoeuvre’, ‘Velocity vs. Rhythms’, ‘The Wahabi War Machine’, ‘Postmodern Anarchists’ and ‘Nomadic Terrorists’, they often reference the work of Deleuze and Guattari. War machines, according to the philosophers, are polymorphous; diffuse organizations characterized by their capacity for metamorphosis, made up of small groups that split up or merge with one another, depending on contingency and circumstances. (Deleuze and Guattari were aware that the state can willingly transform itself into a war machine. Similarly, in their discussion of ‘smooth space’ it is implied that this conception may lead to domination.)

I asked Naveh why Deleuze and Guattari were so popular with the Israeli military. He replied that ‘several of the concepts in A Thousand Plateaux became instrumental for us […] allowing us to explain contemporary situations in a way that we could not have otherwise. It problematized our own paradigms. Most important was the distinction they have pointed out between the concepts of “smooth” and “striated” space [which accordingly reflect] the organizational concepts of the “war machine” and the “state apparatus”. In the IDF we now often use the term “to smooth out space” when we want to refer to operation in a space as if it had no borders. […] Palestinian areas could indeed be thought of as “striated” in the sense that they are enclosed by fences, walls, ditches, roads blocks and so on.’5 When I asked him if moving through walls was part of it, he explained that, ‘In Nablus the IDF understood urban fighting as a spatial problem. [...] Travelling through walls is a simple mechanical solution that connects theory and practice.’6

To understand the IDF’s tactics for moving through Palestinian urban spaces, it is necessary to understand how they interpret the by now familiar principle of ‘swarming’ – a term that has been a buzzword in military theory since the start of the US post cold War doctrine known as the Revolution in Military Affairs. The swarm manoeuvre was in fact adapted, from the Artificial Intelligence principle of swarm intelligence, which assumes that problem-solving capacities are found in the interaction and communication of relatively unsophisticated agents (ants, birds, bees, soldiers) with little or no centralized control. The swarm exemplifies the principle of non-linearity apparent in spatial, organizational and temporal terms. The traditional manoeuvre paradigm, characterized by the simplified geometry of Euclidean order, is transformed, according to the military, into a complex fractal-like geometry. The narrative of the battle plan is replaced by what the military, using a Foucaultian term, calls the ‘toolbox approach’, according to which units receive the tools they need to deal with several given situations and scenarios but cannot predict the order in which these events would actually occur.7 Naveh: ‘Operative and tactical commanders depend on one another and learn the problems through constructing the battle narrative; […] action becomes knowledge, and knowledge becomes action. […] Without a decisive result possible, the main benefit of operation is the very improvement of the system as a system.’8

This may explain the fascination of the military with the spatial and organizational models and modes of operation advanced by theorists such as Deleuze and Guattari. Indeed, as far as the military is concerned, urban warfare is the ultimate Postmodern form of conflict. Belief in a logically structured and single-track battle-plan is lost in the face of the complexity and ambiguity of the urban reality. Civilians become combatants, and combatants become civilians. Identity can be changed as quickly as gender can be feigned: the transformation of women into fighting men can occur at the speed that it takes an undercover ‘Arabized’ Israeli soldier or a camouflaged Palestinian fighter to pull a machine-gun out from under a dress. For a Palestinian fighter caught up in this battle, Israelis seem ‘to be everywhere: behind, on the sides, on the right and on the left. How can you fight that way?’9

Critical theory has become crucial for Nave’s teaching and training. He explained: ‘we employ critical theory primarily in order to critique the military institution itself – its fixed and heavy conceptual foundations. Theory is important for us in order to articulate the gap between the existing paradigm and where we want to go. Without theory we could not make sense of the different events that happen around us and that would otherwise seem disconnected. […] At present the Institute has a tremendous impact on the military; [it has] become a subversive node within it. By training several high-ranking officers we filled the system [IDF] with subversive agents […] who ask questions; […] some of the top brass are not embarrassed to talk about Deleuze or [Bernard] Tschumi.’10 I asked him, ‘Why Tschumi?’ He replied: ‘The idea of disjunction embodied in Tschumi’s book Architecture and Disjunction (1994) became relevant for us […] Tschumi had another approach to epistemology; he wanted to break with single-perspective knowledge and centralized thinking. He saw the world through a variety of different social practices, from a constantly shifting point of view. [Tschumi] created a new grammar; he formed the ideas that compose our thinking.11 I then asked him, why not Derrida and Deconstruction? He answered, ‘Derrida may be a little too opaque for our crowd. We share more with architects; we combine theory and practice. We can read, but we know as well how to build and destroy, and sometimes kill.’12

In addition to these theoretical positions, Naveh references such canonical elements of urban theory as the Situationist practices of dérive (a method of drifting through a city based on what the Situationists referred to as ‘psycho-geography’) and détournement (the adaptation of abandoned buildings for purposes other than those they were designed to perform). These ideas were, of course, conceived by Guy Debord and other members of the Situationist International to challenge the built hierarchy of the capitalist city and break down distinctions between private and public, inside and outside, use and function, replacing private space with a ‘borderless’ public surface. References to the work of Georges Bataille, either directly or as cited in the writings of Tschumi, also speak of a desire to attack architecture and to dismantle the rigid rationalism of a postwar order, to escape ‘the architectural strait-jacket’ and to liberate repressed human desires. In no uncertain terms, education in the humanities – often believed to be the most powerful weapon against imperialism – is being appropriated as a powerful vehicle for imperialism. The military’s use of theory is, of course, nothing new – a long line extends all the way from Marcus Aurelius to General Patton.

Future military attacks on urban terrain will increasingly be dedicated to the use of technologies developed for the purpose of ‘un-walling the wall’, to borrow a term from Gordon Matta-Clark. This is the new soldier/architect’s response to the logic of ‘smart bombs’. The latter have paradoxically resulted in higher numbers of civilian casualties simply because the illusion of precision gives the military-political complex the necessary justification to use explosives in civilian environments.

Here another use of theory as the ultimate ‘smart weapon’ becomes apparent. The military’s seductive use of theoretical and technological discourse seeks to portray war as remote, quick and intellectual, exciting – and even economically viable. Violence can thus be projected as tolerable and the public encouraged to support it. As such, the development and dissemination of new military technologies promote the fiction being projected into the public domain that a military solution is possible – in situations where it is at best very doubtful.

Although you do not need Deleuze to attack Nablus, theory helped the military reorganize by providing a new language in which to speak to itself and others. A ‘smart weapon’ theory has both a practical and a discursive function in redefining urban warfare. The practical or tactical function, the extent to which Deleuzian theory influences military tactics and manoeuvres, raises questions about the relation between theory and practice. Theory obviously has the power to stimulate new sensibilities, but it may also help to explain, develop or even justify ideas that emerged independently within disparate fields of knowledge and with quite different ethical bases. In discursive terms, war – if it is not a total war of annihilation – constitutes a form of discourse between enemies. Every military action is meant to communicate something to the enemy. Talk of ‘swarming’, ‘targeted killings’ and ‘smart destruction’ help the military communicate to its enemies that it has the capacity to effect far greater destruction. Raids can thus be projected as the more moderate alternative to the devastating capacity that the military actually possesses and will unleash if the enemy exceeds the ‘acceptable’ level of violence or breaches some unspoken agreement. In terms of military operational theory it is essential never to use one’s full destructive capacity but rather to maintain the potential to escalate the level of atrocity. Otherwise threats become meaningless.

When the military talks theory to itself, it seems to be about changing its organizational structure and hierarchies. When it invokes theory in communications with the public – in lectures, broadcasts and publications – it seems to be about projecting an image of a civilized and sophisticated military. And when the military ‘talks’ (as every military does) to the enemy, theory could be understood as a particularly intimidating weapon of ‘shock and awe’, the message being: ‘You will never even understand that which kills you.’

Eyal Weizman is an architect, writer and Director of Goldsmith’s College Centre for Research Architecture. His work deals with issues of conflict territories and human rights.

A full version of this article was recently delivered at the conference ‘Beyond Bio-politics’ at City University, New York, and in the architecture program of the Sao Paulo Biennial. A transcript can be read in the March/April, 2006 issue of Radical Philosophy.

1 Quoted in Hannan Greenberg, ‘The Limited Conflict: This Is How You Trick Terrorists’, in Yediot Aharonot; http://www.ynet.co.il/ (23 March 2004) 2 Eyal Weizman interviewed Aviv Kokhavi on 24 September at an Israeli military base near Tel Aviv. Translation from Hebrew by the author; video documentation by Nadav Harel and Zohar Kaniel 3 Sune Segal, ‘What Lies Beneath: Excerpts from an Invasion’, Palestine Monitor, November, 2002; http://www.palestinemonitor.org/eyewitness/Westbank/what_lies_beneath_by_sune_segal.html 9 June, 2005 4 Shimon Naveh, discussion following the talk ‘Dicta Clausewitz: Fractal Manoeuvre: A Brief History of Future Warfare in Urban Environments’, delivered in conjunction with ‘States of Emergency: The Geography of Human Rights’, a debate organized by Eyal Weizman and Anselm Franke as part of ‘Territories Live’, B’tzalel Gallery, Tel Aviv, 5 November 2004 5 Eyal Weizman, telephone interview with Shimon Naveh, 14 October 2005 6 Ibid. 7 Michel Foucault’s description of theory as a ‘toolbox’ was originally developed in conjunction with Deleuze in a 1972 discussion; see Gilles Deleuze and Michel Foucault, ‘Intellectuals and Power’, in Michel Foucault, Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews, ed. and intro. Donald F. Bouchard, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, 1980, p. 206 8 Weizman, interview with Naveh 9 Quoted in Yagil Henkin, ‘The Best Way into Baghdad’, The New York Times, 3 April 2003 10 Weizman, interview with Naveh 11 Naveh is currently working on a Hebrew translation of Bernard Tschumi’s Architecture and Disjunction, MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1997. 12 Weizman, interview with Naveh

Eyal Weizman

Podcasts

Cultural Cartography: Roni Horn -

Open Access Project

Ok derridata, if you liked the piece on Deweyless information science, you might also be taken by the following projects (at this stage still very much in their embryonic stage). I think they could be a good supplement for the Cultural Studies Gateway on Acheron's sidebar. Folks such as Donna Haraway, N.Katherine Hayles, Douglas Kellner et al are playing a formative role (I hope they can forgive me for my familial metaphors). One to monitor perhaps:

Open Access for Arts and Humanities

Open Humanities Press

has been launched to promote open access to Humanities scholarship:

Open Humanities Press (OHP) is an open access publisher of contemporary critical and cultural theory. A grassroots initiative by academics, librarians, journal editors and technology specialists, OHP was formed in response to the growing inequality of readers’ access to critical materials necessary for research in the humanities.

OHP is dedicated to the highest intellectual standards and free, unrestricted access in equal measure. Launching in 2008 as a consortium of leading open access journals in continental philosophy, cultural studies, new media, film and literary criticism, OHP is committed to making scholarly works of outstanding quality and challenge freely available to a worldwide audience.

Meanwhile, Hprints has been created to provide an online archive for Arts and Humanities:

Hprints is an Open Access repository aiming at making scholarly documents from the Arts and Humanities publicly available to the widest possible audience. It is the first of its kind in the Nordic Countries for the Humanities.

Hprints is a direct tool for scientific communication between academics. In the database scholars can upload full-text research material such as articles, papers, conference papers, book chapters etc. This means that the content of the posted material should be comparable to that of a paper that a scholar might submit for publication in for example a peer-reviewed scientific journal.

For scholars this is an opportunity to gain longstanding visibility. First of all, it is possible to search and find the paper by defined topics through an Internet search. Secondly, all submitted papers will be stored permanently and receive a stable web address.

This is probably great news for Arts and Humanities scholars, so hopefully the social sciences might feature more prominently as well as time goes on.

Monday 21 April 2008

Sunday 20 April 2008

This American Life

Racial Oppression in the Global Metropolis: A Living Black Chicago History

Excerpt from This American Life

Hypersegregation

Class and Race

"I do not mean to suggest that the great 'Midwest Metropolis' is any more racist than other U.S. cities or the broader national society of which it a part. I hope the first and introductory chapter and the study as a whole will adequately explain why I have focused specifically on my home city and its broader metropolitan area.

"[Racial Oppression in the Global Metropolis: A Living Black Chicago History] does not deny that a significant and accelerated number and percentage of black Chicagoans and Americans have moved into 'bourgeois' middle and upper strata since [Martin Luther] King’s day. At the same time and in a related vein, the title is not meant to suggest that racism is the only significant societal problem or barrier faced by the city’s, region’s, and nation’s disproportionately poor African-Americans. Those people struggle, I think, with what King called 'class issues—issues that relate to the privileged as over against the underprivileged' and which are hardly limited to race. Chicago and the nation’s large number of impoverished blacks are carrying a double burden of race and class, stuck at the twin and interrelated bottoms of the nation’s steep socioeconomic and racial pyramids.

"Their experience surely attests to the fact that, as King told the SCLC, 'something is wrong with capitalism', an economic system that (he explained in 1966 and 1967) 'produces beggars' alongside luxuriant opulence for the privileged few, thereby recommending, King felt, 'the restructuring of the entire society' and 'the radical redistribution of economic and political power.' It attests also to the fact that, as King explained, 'a nation that will exploit economically will have to have foreign investments and everything else, and will have to use its military might to protect them.' It confirms King’s insistence that we 'question the whole society,' (emphasis added) seeing 'that the problem of racism, the problem of economic exploitation, and the problem of war are all tied together. They are the triple evils that are interrelated'.

"One could write a relevant monograph detailing the hidden and ongoing legacy and price of class oppression in and around notoriously business-dominated capitalist Chicago. I personally see little hope for efforts to address racial inequality and oppression that do not ultimately also confront class inequality and oppression, reflecting basic agreement with King’s conclusion, expressed to a white SCLC staffer in a jail cell in Selma, Alabama, in February 1965: 'if we are going to achieve real equality, the United States will have to adopt a modified form of socialism'.

"Still, reasons for hope are evident in the pages that follow. I am convinced that black experience within and beyond the city reflects the inexorable operation of objectively white-supremacist social and historical forces that possess their 'relatively autonomous' race logic within and beyond the supposedly 'color-blind' logics of capital and class hierarchy. I question (my own analytical tradition of) Marxism’s tendency to treat race as a superficial, merely 'superstructural' add-on to deeper, more relevant class-based structures and modes of exploitation. Without denying the critical relevance of class structures and corporate-capitalist political economy, I am unimpressed with the extent to which the operative social forces driving black subordination within and beyond Chicago have become 'color-blind.' I am struck by the significant extent to which racially oppressive white-supremacist forces and structures contain lives of their own. Those structures and forces, I am convinced, shape American capitalism and richly inform the nation’s profoundly uneven patterns of metropolitan development. And they would pose significant problems for any post-capitalist society born of (say) a revolution whose adherents chose to suppress 'race' issues relative to thoroughly legitimate class justice imperatives."

Unseen City of Poverty and Despair

"The book’s title is not meant to suggest that blacks are the only relevant victims of racial oppression in past or (especially) contemporary Chicago, which has become increasingly Asian and (above all) Latino during the last four decades. In a period when massive waves of Asian and Latin American new immigrants have 'rrevocably altered the dynamic of race relations in cities' Chicago’s patterns of racial segmentation and disparity are obviously quite a bit less simply 'lack and white'than they were in King’s day and before.

"Nor is the title meant to deny that whites are critical and centrally involved in the construction of racial oppression within and beyond Chicago, As Marx once said about capital, race is 'a social relationship,' one that is based on the living historical development of unequal power and recurrent conflict. Whites play an active, indeed leading and dominant, role in the construction of that relationship.

"Still, restrictions of time, space, and (frankly) background and expertise have led to me to say relatively little about the Asian and Latino experience with white supremacy in Chicago. At the same time, I hope this book will provide evidence for my judgment that the most truly oppressed victims of structural inequality in racist/capitalist Chicago continue to be disproportionately black. Blacks remain far and away the most truly segregated 'minority' in and around the city as across the nation—a fact that carries enormous significance for the socioeconomic status and life chances of black Chicagoans. I agree, moreover, with Chicago sociologist Michael Maly that 'black-white conflict remains the deep-seated and unresolved core of group relations in the U.S.', despite the blurring of old racial lines by the latest 'new immigration.'

"The title’s use of the word 'black' is meant to insinuate two further and related connotations. The first intended subtext is the city, region, and nation’s darkly disturbing failure to meaningfully apply its proclaimed integrationist and egalitarian ideals to people living in forgotten communities like the Chicago South Side neighborhood of Riverdale, a 97 percent black community area where in 1999 a third of the adults were unemployed and more than half of the children lived at less than half of the federal government’s notoriously inadequate poverty level. Things have certainly worsened there in subsequent years. There are many Riverdales across urban America. Indeed, the community is just one—hardly the most statistically significant—of many examples of highly concentrated and racialized poverty in Chicago and in the city’s south-suburban ring. Such communities are living testament to the persistent presence of King’s 'triple evils' and to what he called the 'perverted priorities' of a nation that spends billions on imperial militarism while millions of disproportionately nonwhite poor struggle just to keep their heads above water in the imperial 'homeland,' the self-described home and headquarters of world 'freedom.'

"The second intended collateral meaning attached to the use of the word 'black' in the title is 'invisible' or, perhaps better, 'unseen.' I am using one particularly relevant urban region to relate and analyze a problem that many of us no long care to acknowledge: communities mired in desperate poverty in dark shadows between the shiny condominium, office, and entertainment complexes of booming, glorious 'global' downtowns and the glittering suburban 'edge cities' on the ever-expanding periphery of the 'global metropolis.'

"To get a more immediately tangible sense of what I mean, travel one summer to catch an unconventionally obstructed view of the spectacular Chicago Air and Water show from one of the eight city neighborhoods that were both 90 percent or more black and home to a child poverty rate of at least 55 percent in 1999. Step out of your car and look at the blight and pain around you. If you peer carefully at the sky, looking especially to the north or east (the city’s poorest and blackest neighborhoods are located in vast hypersegregated stretches on the South and West sides), above and beyond the vacant lots, boarded-up businesses, dilapidated homes, and (perhaps) the angry and defeated people around you, you may spy a super-expensive fighter jet or bomber soaring above the city’s prosperous and predominantly white New North lakefront. There nearly a million mostly (though not at all exclusively) Caucasian city and metropolitan-area residents will be perched along majestic Lake Michigan on the city’s shining Gold Coast. They will be there to feel some 'shock and awe' at the humbling splendor of the spectacular Arab-killing F-16 and B-2 Stealth Bomber—the latter produced by 'Global Chicago’s' own Boeing Corporation. The breathtaking roar of these dazzling war machines may astound you, perhaps especially from a distance, as it contrasts poignantly with the more local noises, like the passing of a distant L-train or the sound of a battered vehicle as it rolls over a broken bottle in a poorly maintained street.

"Reflect that each of these and other displayed weapons of mass destruction will have cost more than enough many times over to feed, clothe, house, and educate all the children in the desolate community where you are briefly, possibly uneasily, stationed. Reflect also that most of the people taking in the show on the lakefront know nothing or next to it about what life is like in that hidden, mysterious, and officially demonized community, whose outskirts many air show attendees will briefly pass in air-conditioned cars on the way back to air-conditioned homes in predominantly white and relatively affluent communities on the suburban periphery. Like the people in Chicago’s Gold Coast and Lincoln Park, most of them live on the right and disproportionately white sides of what King called 'the tragic walls that separate the outer city of wealth and comfort from the inner city of poverty and despair.' Many, if not most, of them have been taught and conditioned to hate and fear the ghetto; to ignore the circumstances that create and sustain the impoverished, black inner city; and, worst of all, to blame the modern black metropolis’ inhabitants for their own precarious position at the bottom of the nation’s steep and interrelated hierarchies of race, place, power, and class."

"What is Racism? Reflections From Global Chicago"

by Paul Street

Preface to RACIAL OPPRESSION IN THE GLOBAL METROPOLIS: A LIVING BLACK CHICAGO HISTORY(July 28, 2007)

From: Paul Street, RACIAL OPPRESSION IN THE GLOBAL METROPOLIS: A LIVING BLACK CHICAGO HISTORY (New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2007).

Dewey or Do We Not - G version

You may have read about him here.

Or listened to him here.

Or viewed him here.

Marshall talked about things the folks at his library have done with designing spaces and systems for users, including the Deweyless library. He also engaged the class with some ideas about taping into user wants, user behaviors and emerging trends. How can we design the best libraries to fit the needs of the community? Moreover, what does the importation of classification models from bookshops say about the commodification of user behaviour and emerging 2.0 trends?

Wednesday 16 April 2008

Societe du Spectacle, La

Director, Guy Debord; editor, Martine Barraque; music, Michel Corrette; project coordinator, Peggy Ahwesh.

[View it!]

Cleaver, Kathleen. Self Respect, Self Defense and Self Determination

[View it!]

Dialectique peut-elle casser des briques, La? (Can Dialectics Break Bricks?)

Virtually the only available example of a situationist use of cinema, this martial arts film presents a teacher and students of a Korean martial arts school pitted against Japanese invaders. Originally produced in Hong Kong, it was rewritten in French as a situationist political philosophical allegorical struggle between village proletarians and bureaucrats. Originally produced as a motion picture by Yangtze Productions in Hong Kong in 1972 as Tang shou tai chuan tao (Crush), directed by Tu Kuang-chi (Doo Kwang Gee). French language version originally produced in 1973. 84

[View it!]

Monday 14 April 2008

Sunday 13 April 2008

The Complex

Here is the new, hip, high-tech military-industrial complex—an omnipresent, hidden-in-plain-sight system of systems that penetrates all our lives. From iPods to Starbucks to Oakley sunglasses, historian Nick Turse explores the Pentagon’s little-noticed contacts (and contracts) with the products and companies that now form the fabric of America. Turse investigates the remarkable range of military incursions into the civilian world: the Pentagon’s collaborations with Hollywood filmmakers; its outlandish schemes to weaponize the wild kingdom; its joint ventures with the World Wrestling Federation and NASCAR. He shows the inventive ways the military, desperate for new recruits, now targets children and young adults, tapping into the “culture of cool” by making “friends” on MySpace. A striking vision of this brave new world of remote-controlled rats and super-soldiers who need no sleep, The Complex will change our understanding of the militarization of America. We are a long way from Eisenhower’s military-industrial complex: this is the essential book for understanding its twenty-first-century progeny.

Review

“This is a deeply disturbing audit of the Pentagon’s influence on American life, especially its subtle conscription of popular imagination and entertainment technology. If Nick Turse is right, the ‘Matrix’ may be just around the corner.”—Mike Davis, author of Buda's Wagon: A Brief History of the Car Bomb

Saturday 12 April 2008

The Wave

No doubt there are compelling reasons to be suspicious of the tacit endorsement by some German filmmakers of the conclusions reached by Milgram and Zimbardo (it will be recalled that "Die Welle" arrives on the scene after "Das Experiment"). The uniqueness of Germany's resurgent past is open to relativisation once it can be demonstrated that the reproduction of authoritarian structures in any setting can license unthinking obedience and callous indifference to human suffering. Small wonder then that Omer Bartov, in his Germany's War and the Holocaust: Disputed Territories, feels compelled to highlight the shortcomings of Milgram's scientific "objectivity". Bartov reveals, with reference to Milgram's notes about his chosen subjects, a whole host of preconceptions which would have coloured his design of the experiment and the evaluation of any data subsequently collected. Indeed, they are appear to be little more than crude sterotypes about ethnicity and gender socialisation for the most part. This leads Bartov to conclude:

Thursday 10 April 2008

Ned Kelly's Colonial Strategem

Both authors place the Kelly outbreak within the broader context of a rural colonial class system which produced enormous antagonism between wealthy large-scale landowners ('Squatters') and impoverished small landowners ('selectors'). Attempts by the State government to encourage greater equity and more of the rural working class to take up farming ( following the end of the Gold Rush ) largely resulted in further disparity in land and resources ownership, as the various land selection acts were easily circumvented by the squatters and used by them to acquire even more land holdings. Moreover, the interests of the wealthy tended to dominate the local power structures. Squatters, for example, often paid the police handsome rewards for cooperating with local Stock Protection Societies and the vigorous prosecution of their so called 'enemies'. The Kelly family was a particular target of squatter James Whitty and the constabulary, who deemed the Kellys as irredeemably criminal. Such persecution only mounted following the radical Victorian Premier Berry's attempt to break the upper classes control of the Upper House and the public services ( including, of course, the criminal justice system ) when he threatened to introduce mass sackings of, among others, the Victorian police forces, following the Upper Houses blocking of his governments supply. This threat of sacking resulted in an even closer relationship of interest between graziers and police, and also encouraged the radicalisation of police methods as they sought to further prove their effectiveness and worth to government. For the Kellys this meant an increase in special police attention.

Further rural stresses were produced by the onset of drought and an early form of modernity as the advent of the railway, for example, isolated those communities of the North East that were bypassed, and the introduction of new technologies, the costs of which were beyond the means of many poorer farmers who were desperate to make their small land holdings viable. Hence, the symbolic significance of the Kelly gang manufacturing their body armour out of the unproductive technology of plough share boards.

All of the above Jones and Mcquilton use to suggest that the actions of the Kelly gang, and the support of a large sympathiser network used by the gang to evade capture for some twenty months, was not just some simple act of lawlessness, but rather a "semi-political" form of social resistance. Jones, in fact, was the first author to argue that Ned and the gang eventually planned (however vague and naive) the formation of a republic for the discontented rural poor (and not just confined to Irish Australians) of North East Victoria. He argues that the famous Jerilderie Letter foreshadows such a concept:

It will pay the government to give those people who are suffering innocence justice and liberty if not I will be compelled to show some colonial strategem which will open the eyes of not only the Victorian police and inhabitants but also the whole British army. No doubt they will acknowledge their hounds were barking at the wrong stump, and that Fitzpatrick will be the cause of greater slaughter to the Union Jack than St. Patrick was to the snakes and toads in Ireland.

Furthermore, the whole Glenrowan siege itself, Jones maintains, can only be understood as the first vital step towards the realisation of this new republic: the planned killing of the trainload of police, and the capture of the senior police officers for use as hostages; the intention to bail up several local banks to help fund the new movement ; the use of fireworks to signal to the armed sympathisers the commencement of the uprising; Ned's leaving of the Ann Jones Inn to warn the supporters to leave once the failure of the siege was apparent, etc.

Wednesday 9 April 2008

Philosophica Americana

"It is time to do something else"

"In a New Generation of College Students, Many Opt for the Life Examined"

"Once scoffed at as a luxury major, philosophy is being embraced at Rutgers and other universities by a new generation of college students who are drawing modern-day lessons from the age-old discipline as they try to make sense of their world, from the morality of the war in Iraq to the latest political scandal. The economic downturn has done little, if anything, to dampen this enthusiasm among students, who say that what they learn in class can translate into practical skills and careers. On many campuses, debate over modern issues like war and technology is emphasized over the study of classic ancient texts.

"Rutgers, which has long had a top-ranked philosophy department, is one of a number of universities where the number of undergraduate philosophy majors is ballooning; there are 100 in this year’s graduating class, up from 50 in 2002, even as overall enrollment on the main campus has declined by 4 percent".

"At the City University of New York, where enrollment is up 18 percent over the past six years, there are 322 philosophy majors, a 51 percent increase since 2002.

"'If I were to start again as an undergraduate, I would major in philosophy,' said Matthew Goldstein, the CUNY chancellor, who majored in mathematics and statistics. 'I think that subject is really at the core of just about everything we do. If you study humanities or political systems or sciences in general, philosophy is really the mother ship from which all of these disciplines grow.'

"Nationwide, there are more colleges offering undergraduate philosophy programs today than a decade ago (817, up from 765), according to the College Board. Some schools with established programs like Texas A&M, Notre Dame, the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, now have twice as many philosophy majors as they did in the 1990s."

"David E. Schrader, executive director of the American Philosophical Association, a professional organization with 11,000 members, said that in an era in which people change careers frequently, philosophy makes sense. 'It’s a major that helps them become quick learners and gives them strong skills in writing, analysis and critical thinking,' he said.

"Mr. Schrader, an adjunct professor at the University of Delaware, said that the demand for philosophy courses had outpaced the resources at some colleges, where students are often turned away. Some are enrolling in online courses instead, he said, describing it as 'really very strange.'

"'The discipline as we see it from the time of Socrates starts with people face to face, putting their positions on the table,' he said.

"The Rutgers philosophy department is relatively large, with 27 professors, 60 graduate students, and more than 30 undergraduate offerings each semester. For those who cannot get enough of their Descartes in class, there is the Wednesday night philosophy club, where, last week, 11 students debated the metaphysics behind the movie 'The Matrix' for more than an hour.

"An undergraduate philosophy journal started this semester has drawn 36 submissions — about half from Rutgers students — on musings like 'Is the extinction of a species always a bad thing?'

"Barry Loewer, the department chairman, said that Rutgers started building its philosophy program in the late 1980s, when the field was branching into new research areas like cognitive science and becoming more interdisciplinary. He said that many students have double-majored in philosophy and, say, psychology or economics, in recent years, and go on to become doctors, lawyers, writers, investment bankers and even commodities traders.

"As the approach has changed, philosophy has attracted students with little interest in contemplating the classical texts, or what is known as armchair philosophy. Some, like Ms. Onejeme, the pre-med-student-turned-philosopher, who is double majoring in political science, see it as a pre-law track because it emphasizes the verbal and logic skills prized by law schools — something the Rutgers department encourages by pointing out that their majors score high on the LSAT.

"Other students said that studying philosophy, with its emphasis on the big questions and alternative points of view, provided good training for looking at larger societal questions, like globalization and technology."

"In a New Generation of College Students, Many Opt for the Life Examined"

by Winnie Hu

The New York Times

Published: April 6, 2008

"What constitutes an instrumentalized classroom? Perhaps one of the most conspicuous signs of such a classroom is the subordination of the instructional materials to the survey paradigm. A feature of postsecondary education in the United States since the forties, a survey course, regardless of discipline, almost invariably means that a wide range of materials will be examined from an unspecified vantage point for the duration of the course. In literary departments, surveys typically function to introduce students to national, historical, or generic fields ('Survey in British Literature,' for example). The paradigm recommends itself for its efficiency. The survey course covers a lot of ground quickly, and it can be taught with an incredibly high student-to-teacher ratio. Moreover, it encourages precisely the sort of histrionics on the part of teachers that create the impression of pluralism and the 'free marketplace of ideas' for students—people who are regarded by their teachers as simultaneously empty vessels and indisputable authorities on 'what they like.' To be sure, students often enjoy such courses, but less because they are indeed successful than because their 'exposure' to a field of knowledge can be orchestrated so that the discovery of their 'ignorance' becomes indistinguishable from the pleasure their instructors take in being smarter than those who are, by their instructor’s own definition, incapable of seriously evaluating his or her intelligence. This, of course, does not distinguish survey courses from other large lecture courses.

"What gives the idealism latent in the survey paradigm its political charge is the fact that, in the name of providing a general exposure to a subject area that should open up students’ choices, it consolidates and gives institutional legitimacy to the epistemological assumptions students have been hailed with since elementary school—assumptions that are demonstrably narrow and thus incapable of promoting open choices. The assumptions animating idealism are restrictive because they contain as an implicit foundational claim the notion that the sphere of ideas is autonomous (i.e., separate from society and material history) and determinant in the last instance (i.e., ideas make the world go around). It is because ideas are assumed to make the world go around that partisans of survey courses believe that it is responsible to present the sphere of ideas as that which enables a historical period to cohere. It is not a compromise for the sake of pedagogical expediency that motivates this focus—after all, other sorts of courses and major requirements can be imagined—what motivates this focus is a belief in idealism as such. And while it is true that surveys often deal with history,they do so in a manner consistent with the tenets of idealism. This means two things: on the one hand, it means that history is reduced to what we refer to as intellectual history—a reduction that automatically privileges the experiences of those able to give their experiences intellectual expression, and that simultaneously excludes or renders impertinent all otherwise contemporaneous experiences. On the other hand—and this is perhaps the most decisively restrictive aspect of idealism—its approach to history requires that the discourses of intellectual expression be seen as instruments of an intelligence that manipulates them from an ontological elsewhere. In other words, cultural discourse is not only treated as merely historical in the sense of engaged in the day-to-day struggle for existence, but it is also seen as ultimately incapable of infecting the mind with matter. In effect, survey courses, even when they are historical at the level of content, are ahistorical at the level of pedagogical articulation because they proceed as though 'great ideas' engage other 'great ideas' in some timeless sphere where material history never enters. When this arrangement is mapped onto the typical format of an undergraduate lecture, where the mind of the teacher expresses itself in front of what is, on one level, a secretarial pool devoted to materializing his/her ideas (one thinks here of Saussure’s students), the problematic political effects of survey courses are made particularly clear.

"In learning to survey, students absorb a lesson about their relation to knowledge, a lesson that, not surprisingly, is fully coincident with capitalist ideology: those who are in a position to sense the truth of the idea that mind dominates matter learn not only that this idea has always been true, but that it must be true—for if it were not simply a matter of truth (a concept that ambiguously and therefore conveniently refers both to a place and a condition), then one would have to come to terms with the power relation within which this idea has been made to appear true. Idealism is designed to shield truth from power by making the former apply to a sphere of existence that maintains what power it has by denying that power affects this sphere in any way. This is how even the most radical critiques of capitalist patriarchy are instantly neutralized—they are treated as more “great ideas,” a fact that suggests yet another way surveys are inherently restrictive, namely, they are incapable of being effectively critical of the context in which they are offered. For if we agree that being effectively critical has something to do with empowering students to change their social relations, then a course that essentially reproduces the existing social relations within its own organizational dynamics not only cannot be critical, but actively contributes to a maintenance of the status quo. Such a result can hardly be construed as either neutral or open, and in this respect survey courses are indeed problematic even on their advocates’ own terms. To insist, as some proponents of survey courses no doubt will, that one can override the limits of the model through “creative” design, is to fall back into idealism. Specifically, such an insistence relies on the notion that one can simply escape the history embedded in the model, bypassing the domains of the term’s derivation, the relations implicit in the very concept of an overview, the tradition of its institutionalization, and so forth, merely by thinking about things differently. This is not to say that educators are purely passive bearers of what has preceded them, but if we are in some sense capable of historical agency, why should we waste our energies trying to revitalize a patently deficient paradigm? It is time to do something else."

"Survey and Discipline: Literary Pedagogy in the Context of Cultural Studies"

John Mowitt

Saturday 5 April 2008

Crude Awakenings from "preachy" comix

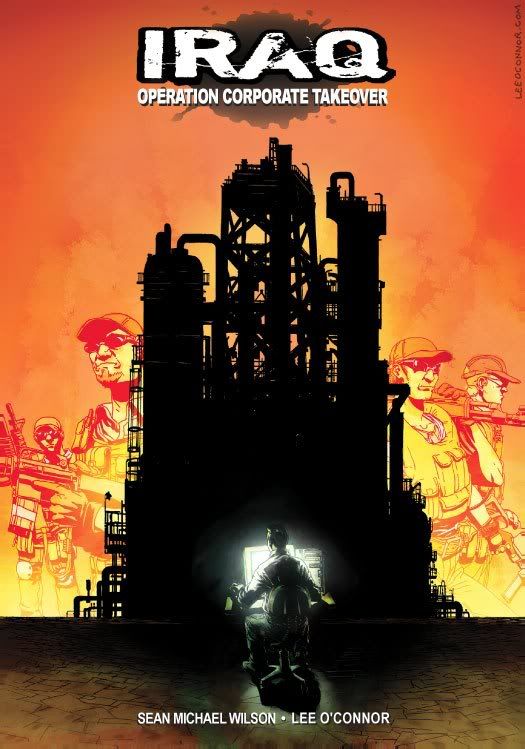

Iraq: Operation Corporate Takeover

War on Want has published Iraq: Operation Corporate Takeover, a cutting edge graphic novel about the corporations who are profiting from the conflict in Iraq.

The comic, created by Sean Michael Wilson (script writer) and Lee O' Connor (illustrator), show that amid the daily violence suffered by Iraqis, oil companies and the US and UK governments are taking advantage of the country’s weakness to secure long-term control over Iraq’s enormous oil reserves. In addition, Private Military and Security Companies (PMSCs) are making a killing in Iraq, while remaining unaccountable for countless human rights abuses and deaths by mercenary soldiers. The comic paints the picture of one young Iraqi man’s efforts to understand and cope with this new reality – and do something about it!

Crude Awakening: The Oil Crash